Flint at the Purple Rose

Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner used to do a routine called “The 2000 Year Old Man.” In it, Reiner was a reporter interviewing Brooks, a man from ancient times. It was largely adlibbed with the reporter deftly setting the premise with genuinely curious questions and the old man providing outrageous answers (in a thick Yiddish accent).

One of my favorite bits was the question of a national anthem. The old man claims to have created the very first national anthem, clarifying that they didn’t actually have nations at that point — just groups of people who lived in caves.

The reporter: “Do you remember the national anthem of your cave?”

The old man: “I certainly do. I’ll never forget. You don’t forget a national anthem.”

The reporter: “Well, please, let us hear it.”

The old man (singing without hesitation): “Let them all go to hell, except Cave 76!”

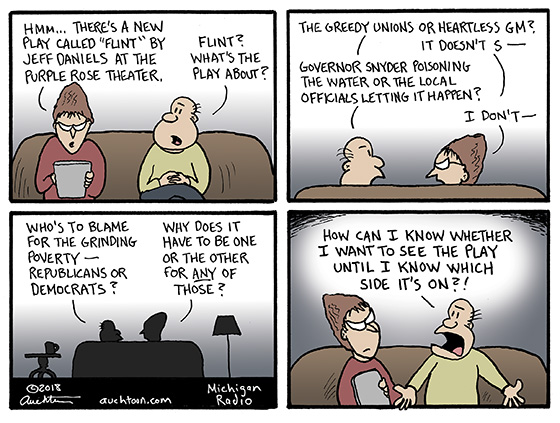

It’s just a brilliant, brilliant piece of satire that lampoons the dark side of our natural inclination toward tribalism and (by extension) nationalism. I was aiming at the same target with the cartoon (fully aware it would fall well short of Brooks & Reiner).

There are plenty of preconceived notions of why Flint is the way it is. And tribalism solidifies these notions, pushing us to identify with our type, our group, our team. Alignment becomes the first priority and soon we are forming opinions about experiences before actually having the experiences.

In the press release for Flint, Jeff Daniels describes his intention for the play: “Flint will bring you up close and personal with the play’s four characters. I want you in the room with them. I want you to feel what they’re feeling.” It’d be a shame to miss out on understanding the Flint experience better because we think that we already know everything about it.